Central Diabetes Insipidus Growth Impact Calculator

Growth Impact Analysis Results

Quick Takeaways

- Central diabetes insipidus (CDI) results from a lack of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) from the brain.

- ADH deficiency disrupts water balance, leading to chronic dehydration and elevated plasma osmolality.

- Persistent dehydration can blunt the release of growth hormone (GH) and lower IGF‑1, stunting growth in children.

- Proper diagnosis requires blood, urine, and MRI tests; treatment with desmopressin restores water balance and supports normal growth.

- Monitoring growth parameters alongside endocrine labs is crucial for long‑term outcome.

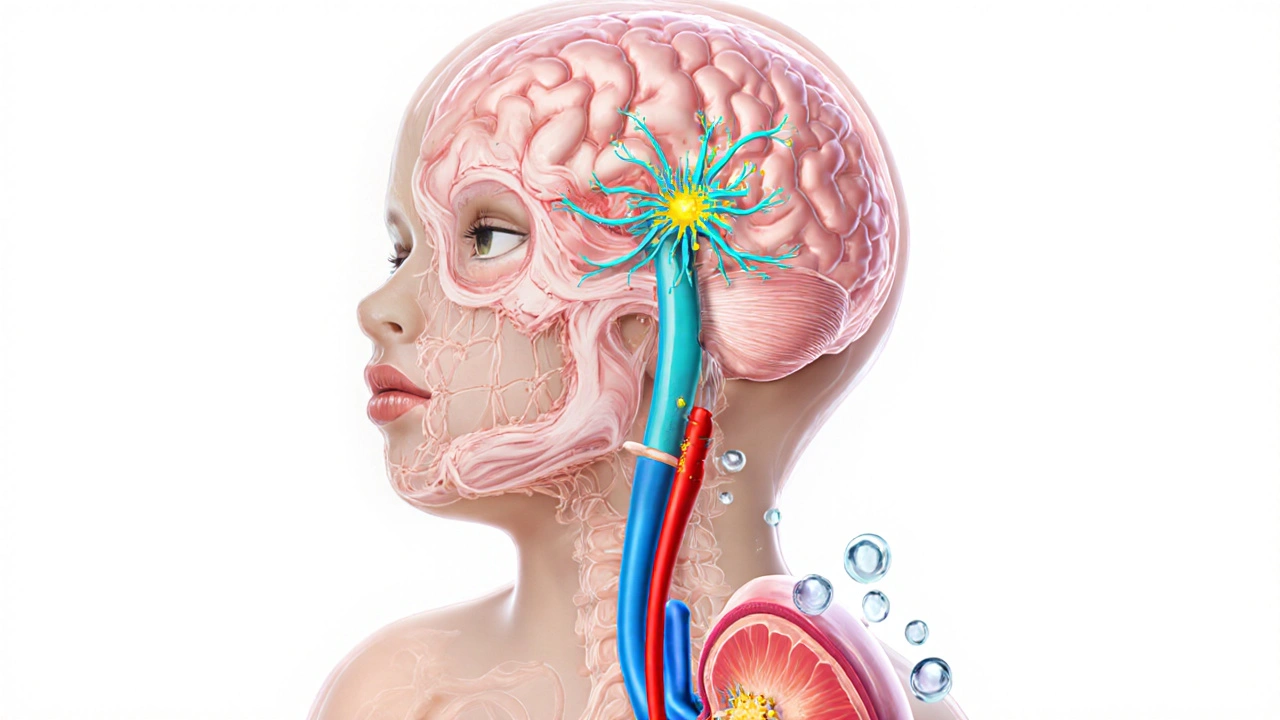

When the brain’s pituitary gland a pea‑sized organ at the base of the skull that releases multiple hormones fails to release enough antidiuretic hormone (ADH), a condition called central diabetes insipidus can develop. ADH, also known as vasopressin the hormone that tells kidneys to re‑absorb water, is produced in the hypothalamus the region that controls thirst, temperature, and hormone secretion. Without enough ADH, the kidneys flood the body with dilute urine, forcing the person to drink constantly.

While the classic symptoms-excessive thirst (polydipsia) and large volumes of urine (polyuria)-are obvious, the hidden link to growth disorders any condition that interferes with normal height gain or skeletal development often goes unnoticed until a child falls behind height percentiles.

Why Water Balance Matters for Growth

Growth in children is driven by a cascade: the hypothalamus releases growth‑releasing hormone (GHRH), the pituitary gland secretes growth hormone (GH) a peptide that stimulates growth of bone and muscle, and the liver converts GH into IGF‑1 insulin‑like growth factor‑1, the main mediator of skeletal growth. This axis is highly sensitive to the body’s hydration status.

When CDI causes chronic dehydration, plasma osmolality rises. The elevated osmotic stress triggers cortisol release and suppresses GHRH, leading to lower GH pulses. Studies from 2023‑2024 show that children with untreated CDI have average IGF‑1 levels 30% below age‑matched norms, correlating with a 2‑3cm/year reduction in height velocity.

Diagnosing CDI in Kids Who Aren’t Growing

- Collect a 24‑hour urine sample: volume >3L/day and urine osmolality <200mOsm/kg suggest DI.

- Measure serum sodium, osmolality, and ADH levels (or copeptin, a stable ADH surrogate).

- Perform a water‑restriction test followed by desmopressin (DDAVP) administration; a >50% rise in urine osmolality confirms central origin.

- Order an MRI of the brain to look for pituitary or hypothalamic lesions (e.g., germinoma, trauma).

- Screen growth parameters: plot height on CDC growth charts, check growth velocity, and obtain IGF‑1 labs.

Treatment: Restoring Balance and Supporting Growth

Desmopressin (synthetic vasopressin) is the first‑line therapy. It can be given as nasal spray, oral tablet, or melt‑in‑water formulation. Doses are titrated to keep urine osmolality >600mOsm/kg and reduce nightly bathroom trips.

Alongside desmopressin, address growth directly:

- Ensure adequate caloric and protein intake-kids need ~100kcal/kg/day during rapid growth phases.

- Monitor serum IGF‑1 every 3‑6months; if still low after hydration normalizes, consider GH replacement under endocrinology supervision.

- Encourage regular physical activity; weight‑bearing exercise stimulates GH secretion.

Comparison Table: Hormone Profiles in Normal vs. CDI Children

| Metric | Typical Child | Untreated CDI Child |

|---|---|---|

| Serum Sodium (mmol/L) | 135‑145 | 146‑152 (mild hypernatremia) |

| Urine Output (L/24h) | 0.8‑1.5 | 3‑6 |

| Urine Osmolality (mOsm/kg) | >600 | <200 |

| GH Peak (ng/mL, stimulation test) | ≥10 | 5‑8 |

| IGF‑1 (µg/L, age‑adjusted) | Within 10‑90th percentile | Below 10th percentile |

| Height Velocity (cm/yr) | 5‑7 | 2‑4 |

Practical Tips for Parents and Caregivers

- Track fluid intake and urine volume in a notebook; look for patterns over 24hours.

- Schedule regular check‑ups with a pediatric endocrinologist; bring growth charts to each visit.

- If your child complains of frequent headaches or vision changes, request an urgent MRI-some pituitary tumors cause CDI.

- Teach your child to recognize early thirst cues; chronic low‑grade dehydration can feel like ‘just being a bit thirsty.’

- When using nasal desmopressin, keep the bottle upright and store at room temperature to preserve potency.

When Things Don't Improve: Red Flags

Even on treatment, a subset of kids continues to lag in height. Consider these possibilities:

- Incorrect desmopressin dose-under‑replacement keeps osmolality low.

- Concurrent hypothyroidism or cortisol deficiency-both suppress GH.

- Genetic growth‑plate disorders (e.g., SHOX deficiency) that mimic CDI‑related growth delay.

Comprehensive labs (TSH, free T4, cortisol, karyotype) can rule out other contributors.

Future Directions in Research

Recent trials (2024) are testing long‑acting desmopressin formulations that release the hormone over 24hours, cutting the need for multiple daily doses. Early data suggest smoother water balance and modest improvements in IGF‑1 levels, likely because hydration stays more stable.

Gene‑therapy approaches aim to restore ADH‑producing neurons in the hypothalamus. While still experimental, animal models have shown restored ADH secretion and normalized growth curves.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can central diabetes insipidus cause short stature?

Yes. Chronic dehydration from untreated CDI reduces GH pulses and lowers IGF‑1, which can slow linear growth and lead to a short‑stature diagnosis if not addressed early.

How is CDI different from nephrogenic diabetes insipidus?

In CDI the brain fails to make ADH; in nephrogenic DI the kidneys ignore ADH. Desmopressin works well for CDI but has limited effect on nephrogenic DI, which often requires thiazide diuretics.

What tests confirm a diagnosis of central DI?

A water‑restriction test followed by desmopressin administration. A rise in urine osmolality of more than 50% after desmopressin confirms a central cause.

Is growth hormone therapy needed for children with CDI?

Only if IGF‑1 remains low after proper hydration and desmopressin control. The endocrinologist will assess growth velocity before starting GH injections.

Can adult patients with CDI experience growth issues?

Adults don’t grow taller, but chronic dehydration can still affect bone density and muscle mass. Proper treatment improves overall quality of life and reduces fracture risk.

Shivam yadav

October 6, 2025 AT 13:30Thanks for sharing this detailed breakdown. It’s fascinating how a hormone from such a tiny part of the brain can influence a child’s entire growth trajectory. In many cultures we see families overlooking subtle signs like constant thirst, assuming it’s just a habit. Raising awareness helps parents seek timely testing and treatment, which can make a huge difference in the child’s height and overall health. Collaboration between pediatricians and endocrinologists is key to catching these cases early.

pallabi banerjee

October 7, 2025 AT 17:43The hormone balance explanation is clear and easy to follow. It reminded me that staying hydrated isn’t just about feeling good, it actually supports the growth hormone pathway. Simple daily checks of water intake and urine output can alert caregivers before a bigger problem develops. Keeping growth charts handy and comparing them regularly is a practical tip for any parent.

Alex EL Shaar

October 9, 2025 AT 00:43well, that’s a nice bedtime story but let’s get real – most docs still miss CDI cause they’re too busy checking labs. the math in the calculator looks slick yet if you feed it garbage numbers you’ll still get garbage output. also, who’s got time to plot growth charts when you’re juggling work and kids? lol, just say “test urine osm” and move on.

Anna Frerker

October 10, 2025 AT 07:43Looks like another overhyped “tool” that will sit unused on a website.

Julius Smith

October 11, 2025 AT 14:43😂 honestly, if you actually tried it you might find it useful. the quick takeaways are solid and the calculator could save an appointment if used right. 👍

Brittaney Phelps

October 12, 2025 AT 21:43Great info! Definitely share this with anyone handling pediatric endocrine cases.

Kim Nguyệt Lệ

October 14, 2025 AT 04:43The post is informative, however there are several grammatical inconsistencies that need correction. “ADH deficiency disrupts water balance” should be “ADH deficiency disrupts the water balance.” Additionally, the phrase “the brain’s pituitary gland a pea‑sized organ” is missing a verb; it should read “the brain’s pituitary gland is a pea‑sized organ.” These edits will improve readability.

Rhonda Adams

October 15, 2025 AT 11:43Thanks for the clean‑up! 😊 I’ll make sure the next draft incorporates those fixes.

Macy-Lynn Lytsman Piernbaum

October 16, 2025 AT 18:43Reading this makes me think about how often we ignore the silent signals our bodies send. It’s wild that something as simple as staying hydrated can unlock the growth potential locked inside a kid’s bones. 🌱💧 Let’s keep spreading the word so no child gets left behind.

Alexandre Baril

October 18, 2025 AT 01:43As a pediatric endocrinologist, I can confirm that central diabetes insipidus is frequently underdiagnosed in children with growth failure. The mechanism involves chronic hyperosmolarity, which suppresses growth hormone pulses and reduces IGF‑1 synthesis. In practice, I start by measuring 24‑hour urine volume; values exceeding 3 L per day are a red flag. Next, a water deprivation test helps differentiate central from nephrogenic causes. MRI of the hypothalamic‑pituitary region can reveal structural lesions such as germinomas. Desmopressin therapy should be titrated to achieve a urine osmolality above 600 mOsm/kg, which often normalizes serum sodium and improves hydration status. Concurrently, I monitor growth velocity on standard CDC charts, aiming for at least a 2 cm/year increase after treatment initiation. If IGF‑1 remains low despite adequate hydration, a formal growth hormone stimulation test is warranted. Nutritional counseling is also essential; children need adequate protein and caloric intake to support catch‑up growth. Regular follow‑up every 3‑6 months allows adjustments in desmopressin dosing and assessment of growth trends. Family education about recognizing signs of over‑ or under‑replacement is crucial to avoid hyponatremia. Collaboration with nephrologists ensures safe management of electrolyte balance. In my experience, early intervention leads to normalization of height percentiles within two to three years. Lastly, psychological support for the child and family should not be overlooked, as chronic illness can affect self‑esteem. These comprehensive steps form the backbone of effective CDI management in pediatric patients.

Stephen Davis

October 19, 2025 AT 08:43Thanks for the thorough rundown! It’s great to see the step‑by‑step approach laid out so clearly. I’ll definitely keep the urine volume threshold and desmopressin target in mind when evaluating my patients.

Grant Wesgate

October 20, 2025 AT 15:43Interesting read. The integration of endocrine and renal monitoring seems essential for these cases.

Richard Phelan

October 21, 2025 AT 22:43Wow, what a theatrical presentation of a hormone cascade! It reads like a soap‑opera script where ADH is the tragic hero, GH the brooding lover, and IGF‑1 the misunderstood sidekick. Yet beneath the drama lies a genuine clinical challenge that deserves our respect. Let’s cut the melodrama and focus on evidence‑based protocols, shall we?