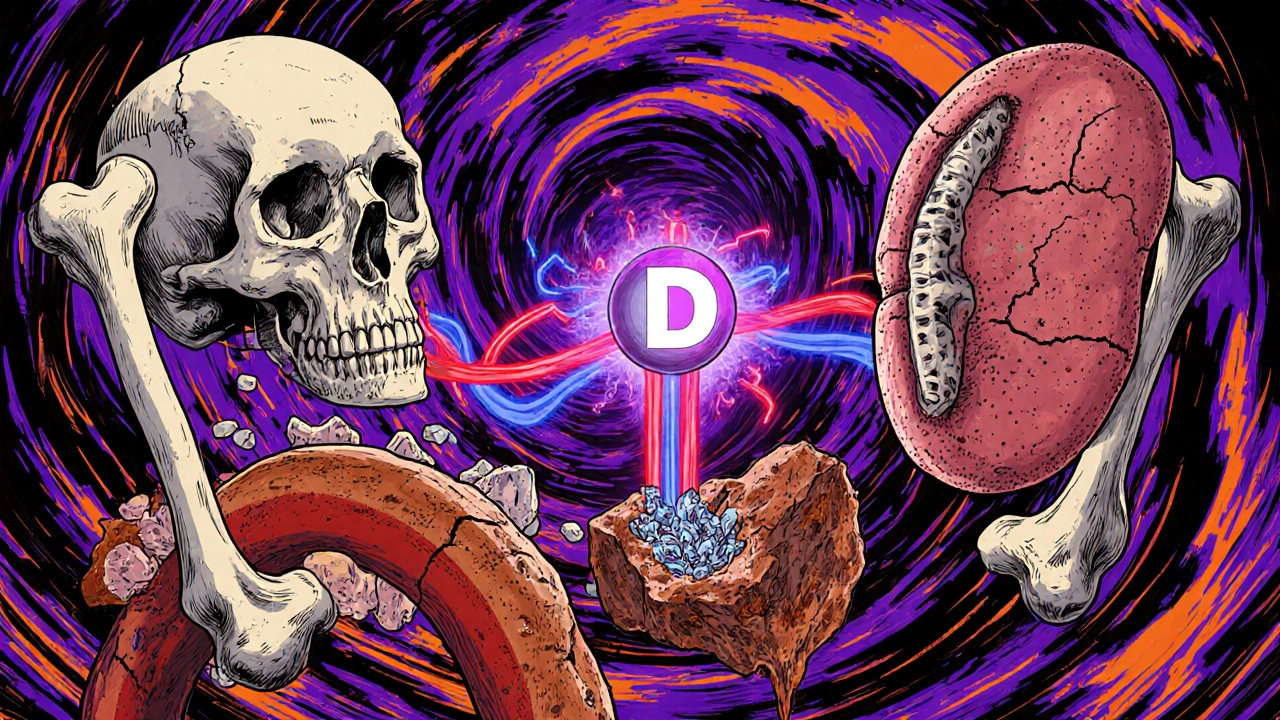

When your kidneys start to fail, they don’t just stop filtering waste. They also lose their ability to keep your bones and blood vessels healthy. This isn’t just about weak bones-it’s a whole-system breakdown involving calcium, parathyroid hormone (PTH), and vitamin D. It’s called CKD-MBD-Chronic Kidney Disease-Mineral and Bone Disorder-and it affects nearly everyone with advanced kidney disease. If you or someone you know has Stage 3 or higher CKD, ignoring this isn’t an option. The risks are real: fractures, heart attacks, and early death are all linked to how these three minerals and hormones interact when the kidneys can’t keep up.

What Exactly Is CKD-MBD?

CKD-MBD isn’t a single problem. It’s a chain reaction. When kidney function drops below 60% (Stage 3), the body starts losing control over phosphate, calcium, and vitamin D. Phosphate builds up because the kidneys can’t flush it out. That triggers a cascade: your bones start leaking calcium into the blood, your parathyroid glands go into overdrive pumping out PTH, and your kidneys stop making active vitamin D. All of this sounds technical, but the result is simple: your bones weaken, your arteries harden, and your heart suffers.

Before 2006, doctors called this condition ‘renal osteodystrophy’-focusing only on bone damage. But research showed the damage goes far beyond the skeleton. Vascular calcification-where calcium deposits build up in blood vessels-is now known to be just as dangerous, if not more so. In fact, 75-90% of dialysis patients show signs of it. That’s why the term changed. CKD-MBD isn’t just a bone disease. It’s a cardiovascular disease with bone symptoms.

The Three Players: Calcium, PTH, and Vitamin D

Think of these three as a trio that used to work together-until the kidneys broke down.

Calcium is the building block of bones and essential for muscle and nerve function. Healthy kidneys help keep calcium levels steady by activating vitamin D and controlling phosphate. But in CKD, calcium levels drop because vitamin D isn’t being made properly. In response, the body pulls calcium from bones to keep blood levels normal. That’s why bones become fragile over time.

PTH is the hormone your parathyroid glands release when calcium dips too low. In early CKD, PTH rises to try to fix the problem. It tells bones to release calcium and tells kidneys to hold onto calcium while flushing out phosphate. But as CKD worsens, the bones stop responding to PTH. This is called ‘PTH resistance.’ So even though PTH levels skyrocket-sometimes over 800 pg/mL-the bones don’t get the signal to rebuild. Meanwhile, high PTH keeps driving calcium into the blood, which then deposits in arteries and heart valves.

Vitamin D is the key that unlocks calcium absorption from food. Your kidneys convert inactive vitamin D (25(OH)D) into its active form, calcitriol. When kidneys fail, that conversion drops by 50-80%. Without active vitamin D, your gut can’t absorb calcium, even if you eat enough. That’s why 80-90% of people with Stage 3-5 CKD are vitamin D deficient. Low vitamin D also makes PTH rise even higher, worsening the cycle.

What Happens to Your Bones?

Bone changes in CKD aren’t what you’d expect. It’s not just osteoporosis. There are three main patterns:

- High turnover disease (osteitis fibrosa cystica): Seen in 20-30% of dialysis patients. PTH is sky-high, bones are constantly breaking down and rebuilding, but the new bone is weak. Fracture risk is high.

- Low turnover disease (adynamic bone disease): The most common type now-50-60% of dialysis patients. PTH is low or normal, but bones barely rebuild at all. They look dense on scans, but they’re brittle. This is often caused by too much calcium-based binder use or overuse of vitamin D analogs.

- Mixed disease: A combination of both, seen in 10-20% of cases.

Here’s the scary part: bone density scans (DEXA) can’t tell the difference. A patient with adynamic bone disease might have normal or even high bone density, but their bones are still prone to breaking. That’s why bone biopsy-the gold standard-is rarely done. Instead, doctors rely on PTH levels, bone-specific alkaline phosphatase, and PINP to guess what’s happening inside the bone.

Why Your Heart Is at Risk

Calcium doesn’t just leave your bones-it ends up in your arteries. This is vascular calcification. It’s like rust forming on pipes, but inside your heart and blood vessels. By Stage 5 CKD, 80% of patients have visible calcification on CT scans. Each year, it progresses by 15-20%. That’s why cardiovascular disease causes half of all deaths in dialysis patients.

Here’s the link: high phosphate and high PTH directly trigger calcium to deposit in vessel walls. Even worse, a hormone called FGF23-released by bones in response to rising phosphate-rises 10 to 1000 times higher in late-stage CKD. FGF23 doesn’t just harm bones; it directly damages the heart muscle, causing thickening and failure. And with Klotho (a protective protein made by kidneys) dropping by 50-70% in CKD, your body loses its main defense against this damage.

Studies show: for every 1 mg/dL rise in serum phosphate, your risk of dying increases by 18%. For every 30% rise in PTH, mortality jumps 12%. And if your vitamin D level is below 20 ng/mL, your risk of death goes up by 30%.

How Is It Diagnosed?

There’s no single test. Diagnosis is based on a mix of blood tests and clinical context.

Key targets from KDIGO 2017 guidelines:

- Calcium: 8.4-10.2 mg/dL

- Phosphate: 2.7-4.6 mg/dL (Stages 3-5), 3.5-5.5 mg/dL (on dialysis)

- PTH: 2-9 times the upper limit of normal for your lab’s reference range

- 25-hydroxyvitamin D: At least 30 ng/mL

Most clinics check these every 3-6 months for Stage 3-4 CKD, and monthly for dialysis patients. But here’s the catch: PTH levels vary widely between labs. What’s ‘normal’ at one hospital might be ‘high’ at another. Always know your lab’s reference range.

Imaging helps too. Plain X-rays can show calcification in arteries, but CT scans (Agatston score) are far more accurate. Still, these aren’t routine. Most doctors rely on blood markers and symptoms-like fractures or chest pain-to guide treatment.

Treatment: It’s Not Just About Drugs

There’s no magic pill. Treatment is about balance-and avoiding overcorrection.

Phosphate control is the first line. That means:

- Diet: Limit phosphate-rich foods-processed meats, colas, cheese, packaged snacks. Aim for 800-1000 mg/day.

- Binders: Take phosphate binders with meals. Calcium-based binders (like calcium carbonate) are cheap but risky-don’t exceed 1500 mg of elemental calcium per day. Non-calcium binders like sevelamer or lanthanum are safer for your arteries but cost more.

- Dialysis: Longer, more frequent sessions help remove phosphate better.

Vitamin D is tricky. Most people with CKD need nutritional vitamin D (cholecalciferol) to raise 25(OH)D above 30 ng/mL. That’s usually 1000-4000 IU daily. Avoid active vitamin D (calcitriol, paricalcitol) unless PTH is above 500 pg/mL. Why? Because they spike calcium and phosphate, worsening calcification.

Calcium should be managed carefully. Don’t aim for ‘normal’ if your phosphate is high. Too much calcium from binders or supplements pushes more calcium into your arteries. The goal isn’t to max out calcium-it’s to keep it in range without pushing phosphate higher.

Calcimimetics like cinacalcet or etelcalcetide can lower PTH without raising calcium or phosphate. They’re used when PTH is above 800 pg/mL and other treatments fail. Etelcalcetide, given as a weekly IV during dialysis, reduces PTH by 45% on average-better than oral cinacalcet.

The Big Mistake: Treating Numbers, Not People

Too many doctors treat CKD-MBD like a math problem: ‘Lower phosphate, raise vitamin D, crush PTH.’ But that’s dangerous.

Aggressive phosphate lowering can lead to malnutrition. Some patients stop eating protein-rich foods because they’re afraid of phosphate-and end up weaker, more inflamed, and more likely to die.

Overusing active vitamin D can cause adynamic bone disease. Patients end up with brittle bones that don’t heal, and no one knows why until they break a hip.

And calcium binders? They’re the most common cause of low-turnover bone disease. If your PTH is dropping too low and your bones aren’t remodeling, it’s likely because you’ve been on too much calcium for too long.

The real answer? Personalized care. A 65-year-old on dialysis with heart disease needs different goals than a 25-year-old with early CKD and no symptoms. The goal isn’t to hit every target-it’s to prevent fractures and heart attacks without starving the body.

What’s New in 2025?

Research is moving fast. New drugs are on the horizon:

- Anti-sclerostin antibodies (like romosozumab) are being tested in CKD patients. Early results show a 30-40% increase in bone density without raising calcium. This could be a game-changer for low-turnover disease.

- Klotho replacement therapy is in animal trials. Giving back this missing protein cuts vascular calcification by 50-60% and improves bone strength. Human trials are expected by 2027.

- FGF23 inhibitors are being studied to break the cycle before phosphate even rises.

But the biggest shift is in timing. New guidelines (2024 draft) say: start monitoring for CKD-MBD at Stage 3-not Stage 5. FGF23 rises years before phosphate does. If you catch it early, you can slow the whole process down.

What Should You Do?

If you have CKD:

- Ask for your phosphate, calcium, PTH, and vitamin D levels every 3-6 months.

- Don’t self-supplement with vitamin D or calcium without testing.

- Read food labels. Avoid anything with ‘phosphate’ or ‘phosphoric acid’ in the ingredients.

- Work with a renal dietitian. They can help you eat enough protein without overloading phosphate.

- Don’t fear PTH. High PTH isn’t always bad-it’s your body trying to protect you. The goal is balance, not elimination.

If you’re a caregiver: Watch for signs of fractures, bone pain, or chest discomfort. Don’t assume it’s just ‘old age.’ In CKD, even minor falls can break bones.

CKD-MBD is complex, but it’s not hopeless. The science is clear: managing calcium, PTH, and vitamin D together-not separately-is the only way to protect bones and hearts. And the earlier you start, the better your chances.

Iska Ede

November 17, 2025 AT 16:47So let me get this straight - we’re telling people with failing kidneys to eat less cheese and colas so their bones don’t turn to dust and their arteries don’t calcify like a rusted pipe? And the solution is… more blood tests? 😂 I love how medicine turns life into a spreadsheet. Also, who decided PTH is the villain? It’s just trying to do its job while the kidneys nap on the job.

Gabriella Jayne Bosticco

November 19, 2025 AT 05:45Really appreciate how you broke this down. I’ve seen friends go from ‘just a kidney thing’ to needing a bone biopsy because no one caught the adynamic bone disease early. It’s scary how normal labs can lie. I always tell people - if your PTH is dropping and you’re still breaking bones, ask about calcium binder overload. It’s not always the disease. Sometimes it’s the treatment.

Sarah Frey

November 19, 2025 AT 20:34While the clinical nuances presented here are both compelling and scientifically rigorous, it is imperative to underscore the necessity of a multidisciplinary approach to CKD-MBD management. The interplay between mineral metabolism, cardiovascular integrity, and nutritional status demands coordinated care involving nephrologists, endocrinologists, dietitians, and, critically, patient-centered communication. Over-reliance on biomarkers without contextual clinical correlation may inadvertently exacerbate iatrogenic harm.

Katelyn Sykes

November 21, 2025 AT 19:04Biggest takeaway? Don’t chase numbers like they’re the goal. My uncle was on calcium binders like candy and ended up with brittle bones that snapped just from sneezing. No one told him his PTH was too low because the lab said it was ‘normal.’ He’s 72 now and walks with a cane because they treated the numbers not the man. Vitamin D? Yeah take it but don’t go full Hulk on calcitriol. And PLEASE read labels - phosphoric acid is in everything from bread to iced tea now

Gabe Solack

November 23, 2025 AT 06:40This is one of the clearest explainers I’ve seen on CKD-MBD. Seriously. The part about FGF23 damaging the heart muscle? Mind blown. 🤯 Also, Klotho replacement therapy in 2027? If that works, we might finally have a real shot at turning the tide. Thanks for sharing the science without the fluff. I’m sharing this with my mom’s nephro team.

Yash Nair

November 24, 2025 AT 01:38USA doctors overcomplicate everything. In India we just give vitamin D3 and tell patient to avoid soda. No fancy binders no biopsies. Your kidneys fail because you eat too much junk food and sit on couch. Why pay for all this testing? We fix it with diet and discipline. No need for 10 blood tests. Just stop eating processed crap. Simple. Why dont you Americans learn from us?

Bailey Sheppard

November 25, 2025 AT 06:45I’ve been managing Stage 4 CKD for five years and this post actually made me feel less scared. I used to think my bone pain was just aging. Turns out it’s probably the PTH and calcium imbalance. I’m scheduling my next labs this week and asking about my vitamin D level. No more guessing. Thank you for making this feel manageable, not overwhelming.

Girish Pai

November 25, 2025 AT 08:00From a nephrology research perspective, the temporal dynamics of FGF23 elevation precede phosphate accumulation by a median of 18-24 months in CKD progression, thereby establishing it as a predictive biomarker of vascular calcification and all-cause mortality. The KDIGO guidelines, while pragmatic, remain underpowered in addressing the non-linear feedback loops between Klotho downregulation and PTH resistance. Future therapeutic paradigms must target the FGF23-Klotho axis as a primary node, not merely downstream effectors.

Kristi Joy

November 26, 2025 AT 22:36For anyone new to this - you’re not alone. I was terrified when my PTH hit 700. But my nephrologist said, ‘We’re not trying to kill your PTH. We’re trying to help your body breathe again.’ That changed everything. Start small. Talk to a renal dietitian. Don’t cut out protein because you’re scared of phosphate. Your body needs it. Find balance, not perfection. You’ve got this.

Hal Nicholas

November 28, 2025 AT 16:35Look, if you’re still reading this after Stage 3, you’re already losing. You didn’t listen to your doctor. You ate carbs. You drank soda. You ignored the signs. Now you’re stuck in this mess with binders and biopsies and blood tests. It’s not the system’s fault. It’s yours. Stop looking for magic pills. Your kidneys failed because you didn’t care enough to change. Now pay the price.